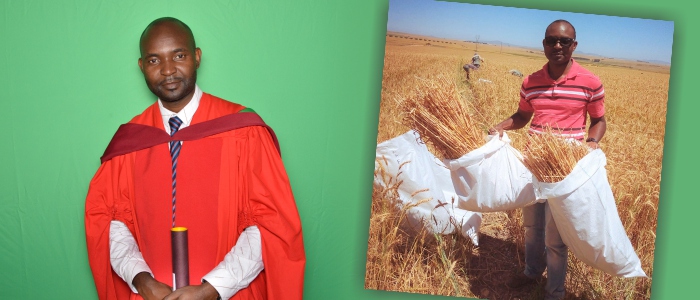

Dr Flackson Tshuma’s passion for using soil both sustainably and productively was nurtured on a plot of land in the midlands of Zimbabwe that his family has farmed on for decades. This former teacher recently graduated with a PhD in Agronomy in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University (SU). Later this year he will hopefully attend yet another PhD graduation ceremony, this time in the United Kingdom, as his is the first dual PhD degree presented by both SU and Coventry University.

“Dr Tshuma was the first to complete a dual PhD between SU and the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience (CAWR), based at Coventry University in the UK, CAWR is a transdisciplinary world leader on research on agroecology and focuses on understanding and developing resilient food and water systems,” says one of his supervisors and chair of the SU Department of Agronomy, Prof Pieter Swanepoel. “This partnership unlocks significant value through complementary expertise from the two institutions.”

Controlling weeds

As part of his PhD studies, Dr Tshuma often visited the Langgewens Research Farm of the Western Cape Department of Agriculture, between Malmesbury and Moorreesburg in the Swartland. It is home to a long-term tillage and crop system experiment, ongoing since 1976. It among others tests the effect of different tillage methods, such as mould boarding, tine-tillage and no-tillage on soil quality and yields.

Dr Tshuma investigated whether in an effort to control weeds there is any merit in sometimes actually allowing some shallow tillage on what is generally considered a no-tillage farm. It is a question that Western Cape farmers practising restorative conservation agriculture – of which no-tillage is a cornerstone principle – have been asking since the 1970s. In the absence of tillage, they may have to use chemicals to control weed growth.

Dr Tshuma among others tested the effect of some shallow tillage every two, three or four years.

“The soil quality was still good afterwards, and production, soil microbial life and enzyme activity in the soil remained the same. However, there was no real benefit in the volume or quality of wheat and canola yielded in the next season.”

Concerning the application of tillage only, Dr Tshuma says, it therefore makes no particular sense to take on the cost and trouble of tilling one’s soil if it doesn’t improved yield.

The use of a mouldboard plough to till the soil to a much deeper level did prevent weed growth. Seeds are buried too deep in the soil to germinate. This ploughing technique however depletes the organic carbon content in the soil, and in turn also microbial and enzyme activity.

Dr Tshuma also investigated whether it would be possible to use less agricultural chemicals to control weeds, pests and diseases on infrequently tilled land or land that is never tilled. The answer was a resounding yes, especially if it was used in combination with environmentally friendly biochemicals.

A cost analysis of what a Western Cape wheat farmer could save in the process must still be done.

However, Dr Tshuma says such an exercise should not be a purely economic one but has to keep benefits to the environment in mind.

“Going into the future, we need to use less chemicals. It would be better for the environment, and also for our own health. We need to consider more environmentally friendly biochemicals, as weeds and pests are increasingly becoming resistant to the products we currently use.

“Overall, results from this study highlight how important it is to reduce both the intensity of tillage and the application of synthetic agrochemicals. Doing so can improve soil quality and crop productivity.”

He says some form of tillage is required to prevent chemical stratification, but this should not be so intensive or frequent as to drastically deplete the soil organic matter stocks. Also, the application of standard synthetic agrochemicals, as conducted in most conservation agriculture systems, can be reduced. It is however risky to completely avoid their use as it could cause smaller crops.

He believes more agroecological farming practices in wheat and canola production in the Western Cape could gradually be introduced by using bio-chemicals. Further research is needed to optimise these approaches.

Some of Dr Tshuma’s findings have already been published in the scientific journal Soil and Tillage Research, and were also presented at recent national conferences.

“After Dr Tshuma presented at a recent information day in the Overberg, one of the farmers attending stood up to thank him for his advice, and for providing new ways of tackling weeds,” Prof Swanepoel remembers a recent heartwarming moment. “It is great to know that his work is helping the local wheat industry.”

Formative years

Dr Tshuma grew up in Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. He fondly remembers how his family would take every opportunity possible to work their land in the community of Zvishavane, some 200km from the city.

He says it lies in a dry region that one might call “the Karoo of Zimbabwe”.

“Farming there taught me how to work wisely with what little water and resources you have. Whatever we do with our soil eventually influences our crops,” he notes wisely.

He developed a keen interest in sustainable agriculture and especially crop production systems. Studies in agriculture was therefore a natural choice. After completing a BSc Honours degree in Animal Sciences from the University of Zimbabwe in 2004, Dr Tshuma worked for Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Agriculture for two years as a regional dairy officer to provide advice to dairy farmers. He also from time to time lectured at local agricultural colleges.

Adult education teacher

Jumping through different sets of hoops that are part and parcel of completing a joint degree counts among the many obstacles that he has had to overcome pursuing his academic dreams.

Coming to South Africa in 2007, he worked as a casual worker in the Strand and Somerset West area before teaching for nearly a decade. He became a part-time maths and natural sciences teacher at Mfuleni High School in 2008, and from 2010 to 2017 taught agricultural sciences and life sciences at the St Francis Adult Education Centre in Langa and Gugulethu.

Thanks to a National Research Foundation (NRF) bursary, he in 2015 could at long last study further. In 2018 he received his MSc degree in Sustainable Agriculture (which was at the time still quite a new degree at Stellenbosch University) after researching how the salt contents of soil influences it quality and the regeneration of medic pastures in the Swartland.

For his PhD he received financial support from the Western Cape Agricultural Research Trust and Coventry University, and received guidance from SU, Coventry University and the Western Cape Department of Agriculture.

Dr Tshuma is currently a volunteer tutor at the Elsenburg Agricultural College, and is a postdoctoral fellow in the SU Department of Agronomy. He is currently writing up scientific articles for publication in international journals.